From the Artistic Director: Mankind

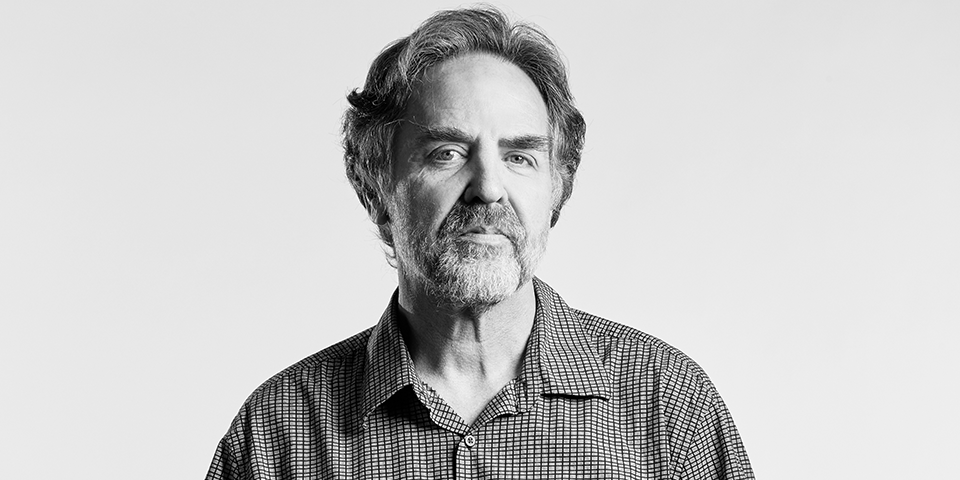

By Tim Sanford, Artistic Director

I hate to call Mankind a satire. We read a lot of satires here at Playwrights Horizons. The majority of them tend to have easy targets, labored setups, broad characterizations, and fleeting shelf lives. The scope of Mankind is as broad as its title. Its starting premise, a world without women, takes dead aim at misogyny, but before you know it, its target starts shifting. Now we’re looking at fascism, then religion, then human nature itself. Its canvas keeps expanding.

An early casualty of Robert O’Hara’s premise is language. We may live in a world of fluid pronouns, but the default structure of language is still built from unfolding binaries. So when one character spins a family yarn about a conflict between his parents when he was a teenager, pronouns and gendered nouns both desert him, leaving us with a monologue both plangent and absurd. He has only inflection to guide him. It reminded me a bit of Caryl Churchill’s amazing Blue Kettle, in which the words “blue” and “kettle” are substituted randomly and ominously into the dialogue as the plot unwinds. In Mankind, however, the semiological reverberations feel a bit tangential. The inadequacies of language seem to highlight instead the force of nature pushing back against the rent, unnatural, womanless world of the play. The men in the play seem to have adapted to their loss. They don’t seem to need women, and adopt female functions and traits when called for. But we also learn this upside down world can only function as a police state.

Mankind’s starting premise, a world without women, takes dead aim at misogyny, but before you know it, its target starts shifting.

One of the more surprising twists to Robert’s tale includes the introduction of religion. Now given that Robert is perhaps the most irreverent playwright in America, you would be excused to expect the play will crank up its satire at this point. And you would not be wrong. But I think perhaps the most important ingredient to a great satire is sincerity. Characters in a satire must embrace the ridiculous circumstances the writer gives to them. And there’s a funny thing about faith. The subjective structure of spirituality — truly earnest, humble spiritual yearning — engenders a faith that pretty much looks the same across all religions. So the theology of the play is fairly ridiculous, but feels nonetheless rather beautiful as well. The play manages to have its satiric cake and eat it too.

But at the end of the day, it’s women who emerge as the star of the play, much as African Americans emerge as the star of the Douglas Turner Ward play, Day of Absence, which Robert cites in his Playwright’s Perspective. Is it possible to write a feminist play with no women in it? And that a woman did not write? I will let the definers answer that question. The rest of us can just marvel and enjoy. Prepare to have your minds blown, my friends.