Backstory: Remembrance of Meals Past

By Adam Greenfield, Associate Artistic Director

The connection between taste and memory is a well-documented mystery. We’ve all had the experience, whether at some truck-stop diner or otherwise dull dinner party, in which the taste, smell, and texture of food unexpectedly fuse mid-bite to trigger some long-forgotten, surprisingly detailed memory of another time and place in our lives: the quality of the light, the song on the radio, the stain on the carpet, and the sense of well-being (or lack thereof) these created in us. For some reason, human evolution has seen to it that food — confronting it, smelling it, tasting it, digesting it — is a uniquely powerful link to the tiny, massive storage warehouse of life experiences in our brains.

There’s a profound lot we don’t understand about memory, and why there is such a connection to food, or how it works, remains mystifying and highly specific to our selves. But we can formulate hints about the process when we look at the mechanics. Any great chef will say the dining experience engages all five senses, but two of those senses, smell and taste, undeniably play the largest roles. The nasal and oral cavities are biologically linked, allowing these senses to react together to chemicals in food, uniting to create the sensation of flavor. When you take a bite of something, your taste buds — each made up of about 100 receptor cells that can distinguish between salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami — send signals to the insular cortex of the brain. What you taste, though, gets exponentially more nuanced when at the same time your olfactory system — millions of smell receptors, of which humans have 450 different types, each able to detect slightly different odor molecules — sends signals to the olfactory bulb. Where this gets interesting: Both our insular cortex (where taste is received) and our olfactory bulb (smell) are connected directly to our amygdala, a brain region that’s highly involved in the processing of emotions and memories; and, similarly, our olfactory nerve is connected to the hippocampus, one of the most important brain structures for memory. In other words, our sense of smell and taste are only one synaptic connection away from emotion and memory. Which, crazily, may just possibly, someday, explain how and why these experiences get tied together.

For some reason, human evolution has seen to it that food — confronting it, smelling it, tasting it, digesting it — is a uniquely powerful link to the tiny, massive storage warehouse of life experiences in our brains.

But reading up on this hypothesis is a bit like reading long ago accounts of sea monsters: concrete knowledge of the phenomenon is still so far from our grasp that every explanation seems to contain equal parts knowledge, bewilderment, and elusiveness. It’s staggering and humbling, what we can’t comprehend about ourselves, and whatever practical data we manage to gain only opens doors to more remote questions; the human condition, it seems, is to be constantly in pursuit of understanding what we experience. And while they take distinctly different approaches, this pursuit is the ongoing project, the shared Sisyphean task, of both artists and scientists. As scientific inquiry inches us closer to an empirical knowledge of the natural and social world, artistic inquiry struggles with the human experience of these. It’s a tight, sultry tango they dance, bringing us ever more perspectives on what, for chrissakes, is going on.

This particular subject of inquiry, the connection of food to memory, shows a startling intersection of the arts and sciences, as the concept of involuntary memory has come to be known as “the Proustian phenomenon” — a moment of perfect recall granted by an incongruous sensory perception. Near the beginning of Proust’s novel Swann’s Way, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past, our narrator breaks from his afternoon habit to eat a petite madeleine dipped in lime-flower tea, a now-famous episode that has been widely recognized since its appearance as not just a milestone moment in modernist literature but as an innovation in the way we understand the workings of our minds.

“Dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory — this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy?”

He digs through his mind, until eventually a memory begins to emerge from his distant past. “I feel something start within me,” he continues, “something that leaves its resting-place and attempts to rise, something that has been embedded like an anchor at a great depth; I do not know yet what it is, but I can feel it mounting slowly; I can measure the resistance, I can hear the echo of great spaces traversed.” And suddenly it reveals itself, and in exquisite detail: the Sundays with his aunt when, before going to mass she would give him a cookie with tea, and what the room looked like, and the flowers in their garden, and the village square, and the country roads leading out of town, and the people he used to know. “But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists,” he continues, “after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.”

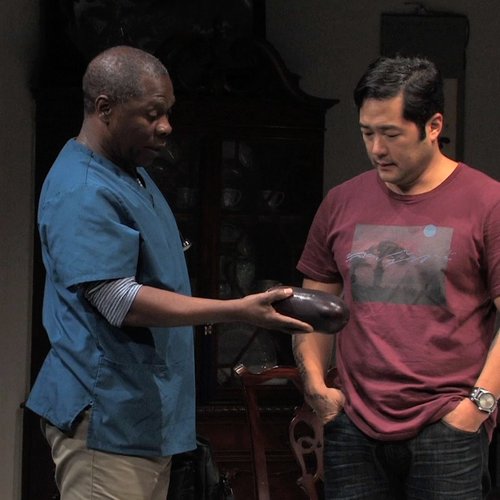

This mystery, the enigmatic Proustian connection between food and memory, is the spark at the center of Aubergine. The force of it crosses continents, languages, and generations to unite the disparate, estranged constellation of characters who gather around an old man in his final days. Extending Proust’s madeleine episode into the lush, lyrical brand of play-worlds Julia Cho cooks up, the preparation of a meal in this play becomes more than just a trigger for emotion or memory, but a way of communicating these: a confrontation, an apology, a seduction, an evasion. Food becomes a language in and of itself. And though these characters may not necessarily grasp its usage — or even really understand it — their pursuit creates a startling glimpse, a new synaptic pathway, into what might be happening inside us.