Julia Cho Artist Interview

Note: This interview contains spoilers about the contents of Aubergine.

Tim Sanford: We co-produced BFE with the Long Wharf in 2005. You hadn’t had a lot of work in New York at that point. I think something at the Workshop?

Julia Cho: There was 99 Histories with the Cherry Lane’s Alternative Mentor Project; that was more like a workshop production. And then I’d had The Architecture of Loss in the basement space of New York Theatre Workshop. (Laughs.) I don’t even know if they produce in that space anymore.

BFE was such a wonderful experience. Gordon [Edelstein] is such a big-hearted guy, and his production had such a lively, youthful feel. Not every co-production is such a happy experience.

Gordon really is a magical figure in my life; he produced BFE at Long Wharf and then soon after did Durango, and both times he magically turned one production into two. He did BFE as a co-production with you then also did Durango as a co-production with The Public.

Did Chay [Yew] direct Durango?

Yes. And I love Gordon to this day because, fairly early in the process of Durango he said to me, “Julia, just so we’re clear on this, we’re not gonna do another Julia Cho play for a while.” And he said it in a very kind way, just to let me know that I shouldn’t have any expectations. Which I appreciated. Then Chay and I went to the O’Neill [Playwrights Conference] to do a workshop of Durango and Gordon just happened to be there. And at the end of the O’Neill he was like, “We’re doin’ the play!” (Laughs.) Which I think is a testament to Chay’s direction.

And to Gordon’s personality. He’s such an enthusiast. Plus that was a wonderful production. Then what was your next production? The Piano Teacher?

I think so.

Which Kate Whoriskey directed at the Vineyard. And then The Language Archive at Roundabout. So you did all four of those plays within, what would you say, like, six years?

Yeah.

Or somethin’ around that?

Yeah.

And then you kind of went away for a while.

Yeah. (Laughs.)

And I missed you.

(Both laugh.)

Thank you. Thank you for missing me. It wasn’t intentional… Although Language Archive was a really hard play for me to write. Not because of subject material or anything like that, but because I felt tapped out. I used up whatever I had left to do The Language Archive and then there was just this cavernous empty storeroom.

I guess I always made the assumption… I’d heard you started a family, so I guess I thought that was it.

I don’t have any better answer than that life just happened. I look back on that period of time of doing plays in New York as this incredible, youthful time. And youthful not just in the number of years, but in my energy. I think it was almost like that problem bands have, where your first album is everything you’ve been thinking about for your entire life up until that point…

Uh-huh.

…And then you make that album and for your second album, you’re like, “Oh my God... It took me 20 years to accumulate the material for album number one; what if it takes me 20 more years for number two?” Although I suppose what ends up happening is that the longer you live the more intense life gets. You can pack a lot of living as you get older into a shorter amount of time. And I think that’s kind of what happened. I stepped away from theater, I moved out of New York and I was just empty for a long time.

I think I actually asked [John] Buzzetti [Julia’s agent] around that time, “Do you think Julia would be interested in a commission?” And I think his response reflected what you’re saying. Like, “She’s not really taking any commissions right now.”

Well I owed commissions. And I spent a lot of that time feeling very guilty about not writing. Which probably in some way hindered the writing too, so that was not a productive emotion to have.

So... When John sent me this play, when he sent me Aubergine, I hadn’t read a new play of yours in a while... So here are the phases of my response...

Okay.

I got all excited.

Okay. (Laughs.)

‘Cause, “Oh, Julia’s writing again!”

(Julia laughs.)

And really thrilled. And then I started reading it and I immediately had an intense personal response to it. And sure in part it brought up a lot of unprocessed feelings I had about my own dad’s passing. But I was also responding to how raw and vulnerable and authentic the emotions are in this play. So I called you up and it all came tumbling out; I just really wanted to produce it. And I knew there was this kind of unacknowledged connection. I knew it was a personal play for you. I think you tacitly acknowledge that in your Playwright’s Perspective in the bulletin when you talk about snacking on ramen with your dad at night. But of course no writers want to talk about the personal roots of their work. Yet it’s of interest to me how writers process what’s inside of them, and what comes out as a surprise to them. And what becomes clear in the process. Would you talk about how this play came to life?

For a lot of the time when I was not writing, when I thought about actually sitting down to write, it felt impossible. It felt like obviously I should write about some of the things that happened, but I really didn’t want to. And I felt maybe it would even be horrible to use the experience. There’s a writer, I think it’s Graham Greene, who said, “There is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer.” And there’s a poet, Stephen Dunn, who wrote a poem where the first line goes, “When Mother died / I thought: now I’ll have a death poem. / That was unforgiveable.”

Huh.

I think for a long time I knew that if I wrote at all, it would inevitably go in that direction… and so it felt better to not even write at all. But one thing that actually helped me was a residency I took at the McCarter. I was slowly trying to get back into writing and this residency was perfect because they just ask you to come and write. There’s no expectation and there’s no obligation to come out of it with anything. So I sort of wrested myself away from my life and did that. And I didn’t actually get much writing done because I was still trying to find my way, but Paula Vogel was there and even though she’s never been a teacher of mine...

Was she there because she’d been invited in the same way?

Yeah, and I just sort of stole a moment with her. I was telling her all about what was going on with me, and she was so kind about it. I was saying, “There’s this big boulder in the way and while I don’t want to write about how hard the years have been, I feel like I can’t write about anything else either.” And she was just really sympathetic and wonderful about it.

I think it’s interesting you ran into Paula when you did. Her breakthrough play, The Baltimore Waltz, famously made artistic use of her relationship with her brother. Did she say anything encouraging about writing about your “boulder” or was it more general encouragement?

Paula had some very specific advice. It had to do with not what I was afraid of writing about — loss, death, etc. — and trying to face and defeat it, but with trying to articulate what it was I actively wanted to write about. She kind of turned my whole problem on its head. It was magic. Because Paula Vogel is magic. I’m convinced of that.

How did Berkeley Rep come into the picture?

Madeleine Oldham [Berkeley Rep’s Director of The Ground Floor/Resident Dramaturg] had devised this crazy project of all these different writers writing short plays about food, which sounded really appealing because, as you know, there’s really no market for short plays. So it felt very safe, like, “Oh, okay. Who’s ever gonna see that?” (Laughs.) And also it was Berkeley, and it’s food, so it’s not like writing about anything that seemed dark or sad. It was like, “Food is wonderful! Food makes everyone happy!”

(Both laugh.)

So I almost looked at it as an exercise. But the funny thing, of course, is that as soon as I started thinking about food I started thinking about family and of what I eat and why. And then food quickly became about memory and what meals I’d had and why I remembered the meals I remembered… and then I found myself writing about this guy who’s a chef and then I realize, “He’s losing his dad.” It was all the stuff that I wasn’t going to write about or didn’t know how to write about. It was kind of like the mind tricking itself. So how lucky I am that Berkeley happened to call me up.

So how long was it?

It was a 20-minute play.

Was it performed?

No, I think we had a reading of all the plays just for ourselves to hear, and it was really wonderful to be with the other writers. And see how they approached the topic. But I feel like I ended up using it to do something totally different.

Did you realize it was the seed of a larger play right away?

No. I had that kernel of 20 pages and I realized that it would never have a life. And I wondered if there was more to it. I had these characters and I had a sense that they had a bigger story.

Were there scenes that are still in the play?

Yeah. The relationship between Ray, his father, and Lucien — that’s really what the original, shorter version was. It was a distillation, I would say, of the play. And it’s still all there now.

So Lucien’s personal story was pretty similar to what we have now?

Yes.

So what was the next step? Did you have to talk to Madeleine first?

I did talk to Madeleine first, because I wanted to see if they were interested in the expansion, and she said yes. But it was very much an experiment. I really felt like I was in one of those mines, and you have your pick axe, and you’re like, “Oh, there’s a little tiny vein of gold here, let’s just see where it goes, and maybe it will lead to a larger pay load of ore, but maybe it’ll just peter out.” I really didn’t know at that point.

But the main thing is you’re writing again.

Yeah, I reached a point where I felt, “This is ridiculous that I haven’t written a play in so long.” And what I did on just the most practical level was, I wrote out a contract that said, “I promise I will write every single day until I have a play.” And then I signed it and I dated it. And I kept the promise. But the way I put it to myself was, “I cannot promise that I’m gonna spend two hours a day on this or more, but I promise every day to touch the play until it’s done.” So there were literally days where I would just open my computer, read a sentence, maybe change a word, and then that was all I had time for that day. (Laughs.) But what I found was that I started to have a real respect for the way that we, as human beings, live on a 24-hour cycle because of the sun and the moon, or whatever you want to call it. I really did find that if I went too far beyond 24 hours — if I would touch it at 8 AM one day and then 8 PM the next — it actually changed. I found that the ideal was if I touched it at least once within a 24-hour period.

Would you find that you were carrying things in your unconscious that would come out when you sat down to write? Or did you actually have to be writing for the story to develop?

Well, there are always discoveries in the writing, of things coming out that I didn’t know I was carrying. But I wouldn’t say I developed the story or even thought about it much when I was away from it. I think the fact that I knew I would be touching it physically once a day meant that I could give myself the luxury of not having to carry it in between. Consciously anyway.

So when it comes to actually writing scenes, what happens?

I go linearly, so I began with the first part of the play and then just moved forward to see if there were pockets of other scenes or other people that came up. The biggest turning point for me was the arrival of the uncle. I remember the day the uncle showed up because I was writing scenes with Ray and Lucien, and Lucien starts asking, “Is anyone else coming?” And I started to think, “Oh, yeah! There’s a family that would come!” And then I had a moment. Up until this point in my career, I’d written plays in such a way that I didn’t actually have any Korean people or people speaking Korean simply because I don’t know Korean. I hear Korean all the time; relatives speak it, it’s sort of in the background. But in my plays, if there were Korean characters, I always had them communicating in English, like someone Korean talking to their Korean American child or two Korean Americans talking to each other. But it was very clear to me if the father has a relative, obviously that person is going to be Korean. And speaking in Korean. And I spent a lot of time thinking, “But that’s impossible because I do not speak it.” And I didn’t want to have him show up and speak broken English. I’ve done it, but it’s never fun to take intelligent, articulate people and make them speak in a broken tongue. And so I had a moment where I stopped because I literally felt like there was a knock at the door, and I knew there was a Korean behind that door.

(Both laugh.)

I was like, “I’m sorry, but I cannot let you in! I do not know how to write you! Please go away!” And I remember getting up from my desk and pacing. “What do I do? What do I do?” I kept thinking, “Are there ways in which I could have him speaking in English, but we would understand he’s speaking Korean?” Then I was like, “No, because you can’t replicate the grammar.” It wouldn’t give you an honest sense of the actual language, how unlike English it really is. Until basically I just reached a point where I thought, “I’m just gonna write it in English ‘cause that’s the gist of what he’s saying” — and then I did the most cheaty thing I could of think of: if you look at that first draft, there’s an asterisk before all of the uncle’s lines and then a note that says, “Everything after this asterisk is in Korean.” (Laughs.) And I just did that ‘cause I was like, “If I don’t do that, I’m done. I can’t move forward.”

Did you decide then, “I gotta find someone who can write this for me?”

No. At that point, when the uncle arrived, and the asterisks started happening, I thought, “This play now will only exist in my mind because this is an impossibility. I do not know anyone who translates, I do not even know how to go about paying someone to translate. And even if I could find someone, the actor does not exist who could play this part.” And I was obviously wrong, because here we are. But at that time I was 100% convinced that this actor does not exist in this country.

And did Cornelia appear…

After that.

…for her own sake, or partly...

Because of that!

...of the translation problem?

Well, not exactly. She came not to serve me, the playwright, like, “Now I need to have a translator.” It really was more, “Well, if Ray’s got an uncle to call then he’s going to need some help.”

Right.

She really came out of what Ray needed. But, you know, she still doesn’t solve the problem; she’s not really translating for him every moment. Plus then I had Cornelia’s lines that I didn’t know how to write in Korean either.

I could just as easily have guessed that the decision to have Cornelia was more because Ray is emotionally blocked and can’t let anyone love him. Once she appears, she’s integral to the story.

Yeah, but I don’t know if she would have come if the uncle hadn’t come.

So when did you finally decide to find a translator?

I didn’t. I think it was all through the grace of God. (Laughs.) Or divinity because I gave the play to Madeleine and said, “It’s unproduceable. And it’s not because there’s an elephant or I need a helicopter; there’s no such thing as this actor.” And she didn’t believe me. She was like, “Oh you playwright. You’re all so crazy.” So then we did a cold read, but the early readings of the play were all with English speakers. The turning point was when Berkeley decided to move forward and develop it at The Ground Floor, which is this summer workshop where they invite all these projects, and at that point they helped me find a translator. And what was really interesting about it was... I thought it would be really difficult to find a translator, but all these different people started telling me about the same person. I had Sarah Ruhl telling me about her amazing student Hansol Jung. And Madeleine not only knew Hansol; Hansol was coming for The Ground Floor too. She was coming the week before me so Madeleine said, “Let’s see if she can just stay a little longer.” And I think Hansol might have had to go away and then come back because her own career was exploding. But she made the time for this. So then I not only had a translator, someone who was a native speaker in Korean and could also write in English, I also had somebody who had the sensibility for theater, who understood it.

There’s a music to the Korean. It feels like your hand is in there somehow.

One of the great joys of the process of translating was working with Hansol because I had a feel for the Korean and what I wanted it to sound like, but I couldn’t do it myself. To explain, I can only give this story, which is that when I was younger I did a French immersion program at Middlebury. I, who had only had two years of French, was suddenly forced to communicate only in French. And at some point I started having dreams in French. And one of the dreams is I’m at my normal high school and I’m in English class and my English teacher is speaking French. Fluently. And in my dream I think to myself, “Oh my gosh, her French is so good I can’t even understand it!” And I guess that’s how Korean feels to me. I’m not capable of it, and yet there’s some subconscious part of me that understands it better than I consciously know. And to this day when someone speaks Korean to me I really don’t know a lot of what they’re saying and yet it’s totally familiar to me. Somehow that paradox is in the play.

Is that at all true for Ray? Like the uncle has that long speech about his grandmother and Cornelia asks him, “Did you get any of that?” Do you have an opinion about if he’s getting any of it or not?

I always try to go with whatever feels true for the actor, but I think Ray does absorb some of that speech.

Plus I think the rules of the subtitles head us in that direction, don’t they? The way I interpret it, there are subtitles only when Cornelia is present, so only when there is someone who understands the Korean. But in the last scene, at the grave in Korea, there are subtitles for the first time when Ray is alone with Uncle. So that would indicate Ray is getting some of the Korean now. Is that right?

Yeah.

I’m assuming you indicate where the subtitles are present?

Yeah.

Did you ever consider having subtitles for all of Uncle’s lines?

No. I think hearing a language you don’t understand — being bombarded with it, in fact — is just part of Ray’s reality — and mine. But there are moments when Ray, despite not being able to speak the language, can achieve a kind of zone in it. When you’re with somebody who speaks a different language, even if it’s not one you’re familiar with, I would like to think there’s some humanness, some desire to communicate, that allows you to connect, sit together, share some vibration. And certainly those two men have it by the end. I think they’ve earned it.

So the Korean that you grew up with, was it your immediate family?

It was immediate family.

When your parents talked to each other did they talk in Korean?

Yeah. I grew up hearing people talking it all the time. I think, despite the big distance, there was a link between Language Archive and this play because Language Archive was all about, “Why don’t I speak Korean?” How is it possible to be around a language all your life and not pick it up? It boggled my mind. Language Archive poses the question, “Why? Why don’t we speak the tongues of our relatives?” And Aubergine explores the consequences of that in a more immediate way.

So Aubergine started with the emotional connections of food, and then it became a short play about a young man dealing with death of his father...

Mmhmm.

And then, as you expanded it, the Korean uncle came in, the ex-girlfriend came in, and the emotional terrain expands as well — of everything that Ray’s going through...

Yeah.

So he’s gotta deal with his family, he’s gotta deal with his Koreanness, that aspect of his identity, which you just alluded to...

Mmhmm.

Whatever’s blocking him with his girlfriend... There’s one other expansion that happens in the play, which is the character of Diane.

Yeah.

Could you talk about how that came to you?

Diane is actually the oldest part of the play. There was a restaurant in Chicago called Next, which I read about. The creator of this restaurant, Grant Achatz, wanted to recreate a certain time and place. So, if you went there you would have a meal that was, like, Vienna in the 1920’s. And they would meticulously recreate everything down from the 1920’s Viennese dishes to the cutlery... So you would sit down and the entire meal was a recreation of what you would eat in that time and place. And there was a lot of stuff that he did which was about memory, like food that smelled of grass, which would remind you of a fresh cut lawn. So that was a huge inspiration: if I could go to a restaurant and recreate a time and place, what would I want? That was where Diane came from. It was separate from Aubergine, and then once I started writing about food it felt like she belonged in that story.

You mean you were writing about that phenomenon and this character separately? Like, you didn’t know what it was for?

There was a theater in Chicago called the Next Theatre that asked me, “We’re doing this whole benefit on the idea of Next; would you write something about that?” This was actually years before Berkeley came to me. And in looking at the idea of Next, I found this restaurant. And then I started thinking about the patron of that kind of restaurant. And if I couldn’t have Vienna or, you know, Kyoto, what would I want? If I could find the perfect meal, the perfect chef to make certain meals, wow, what a power. So that was Diane’s little monologue and then I somehow never connected with the theater again. I don’t know if the connection got lost but it never got used for anything; it just sat in my computer and then cut to years later and I’m writing about Ray and I’m like, “He’s the chef who could do that!” So then she became part of the whole story. And once that happened, it seemed like she should get her sandwich. (Laughs.) She became this kind of bookend, but I like your way of articulating it much better. It’s not a bookend, but an outer ring.

There are things in her story that resonate. Like her father’s sandwich is kind of like the uncle’s story of the meal Ray’s grandmother made for his father before he left. But that sandwich also recalls the bowl of mulberries Ray makes for Cornelia and the aubergine Ray prepares for Lucien. But also, Diane’s story is very much about dealing with her father’s death.

Tim. You’re getting to all my secrets. I’m gonna have nothing left.

(Both laugh.)

I’m not saying you wrote all these things intentionally. In one of Anne Washburn’s talkbacks, I was complimenting her on a structural feature of Antlia Pneumatica and she said, “I always find the stuff that seems the most logical is the most unconscious.” That the unconscious creates these structures that you really only discover after.

Yeah, I think that that’s absolutely true.

And the other thing about Diane’s monologue is that it sets up all the other monologues about food through the play. Was that a structure you became conscious of as it was emerging?

I don’t know if I was aware of it, but when it came to writing a play for the first time in so long I wasn’t really interested in reinventing the wheel. I was like, “It’s hard enough to just write a play; I don’t know if I can also be formalistically interesting and experimental.” I’ve written other plays with that same structure, where there’s a back and forth between scenes and long monologues. So I don’t know if it was conscious, but it was definitely a form that felt good to me. It was like a sweater I could wear as I was writing. (Laughs.)

There’s one beautiful moment that really jumps out when Uncle sings “Nearer My God to Thee” in English. It reminded me that Christianity is really strong in the Korean community. I think of all the Asian countries, Christianity has the strongest foothold...

I think that’s right. That was a big part of my growing up and I still have a very, very god-fearing family. Faith was another language that was spoken a lot in my home.

It’s a beautiful, intimate, surprising moment, partly because he sings it in English. Would they sing the hymns in English in Korea?

I think the uncle in his day to day life sings hymns in Korean. But there are a handful he knows in English. To me, it isn’t such a stretch. Almost all Koreans speak at least a little English – they’re familiar with its sound, with some words. And it just felt right. I think he chooses to sing in English because he wants to include Ray. And communicate with him in maybe the only way he knows how.

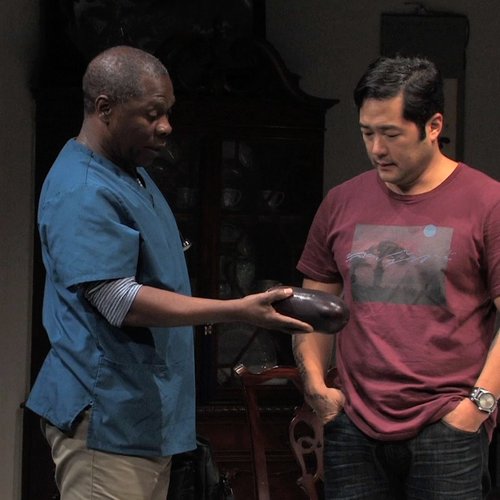

A lot happens in the play after the father dies. The father’s monologue is both surprising and inevitable — of course he gets his own take on food too. And then we have that gorgeous scene with Lucien, when Ray makes the eggplant dish for him and talks about his father’s death. But Ray still has a ways to go on his journey. I think we realize that there are different levels of the story, there’s Ray’s relationship with his father, with his family, with his girlfriend, with his Korean heritage, and with his vocation, his relationship to food. These elements are interconnected, but separate.

I think as humans we are trained to think of death as an end. But the play, I think — I hope — treats it more like a transition. There is one way in which a story exists with a beginning, middle, end. But I don’t think that’s the only kind of story. There is another story where even death can still be the beginning of something. Instead of a linear story, the play to me feels more like a series of concentric circles, stories that are nested in each other. And as the play progresses, each of these stories reaches its own conclusion, in a way that doesn’t cone down into a tight point. Instead, the circles widen, ripple outwards. At least that’s what I hope. But everyone will have their own experience of the play. And I guess my job is not to get in the way.