From the Artistic Director: I Was Most Alive with You

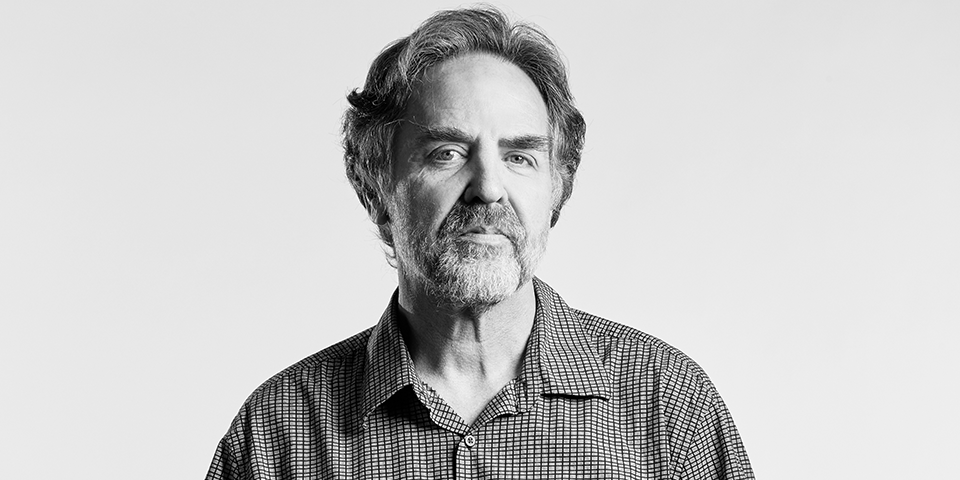

By Tim Sanford, Artistic Director

One summer, when I was talking with a few of my hearing friends, a man, hearing my speech, asked me what kind of accent I had. Fed up with questions of this sort, I replied, “A deaf accent.” He looked confused and asked, “What country is that?” I looked him in the eye and answered: “Deafland.” “Deafland?” he replied, “Where is that?”

“Textual Bodies, Bodily Texts,” Jennifer L. Nelson, from The Aesthetics of ASL

Genius and disease, like strength and mutilation, may be inextricably bound up together.

The Wound and the Bow, Edmund Wilson

Knox: I’m grateful for my family…. And for two, no, three things I used to think weren’t gifts at all: Deafness…. Being gay…. Addiction…. They are gifts… Each brought me great clarity.

I Was Most Alive with You, Craig Lucas

Theater has provided the dominant hearing culture with glimpses into Deaf culture sporadically over the last few decades. Some examples include Mark Medoff’s Children of a Lesser God, productions by Deaf West Theatre, and Nina Raine’s Tribes. Craig attributes the origins of this play to a close relationship he developed with a Deaf woman 20 years ago. And that interest was rekindled, professionally, when he went to Tribes and was so moved by Russell Harvard’s electrifying performance that he found himself pledging to write a play for him. As he reimmersed himself in Deaf culture, he soon learned that while the aforementioned theatrical works represented milestones for the Deaf community, these productions were also viewed as being pitched to hearing audiences. As I Was Most Alive with You began to take shape, he vowed to tell this story in a way that would feel as accessible to Deaf audiences as hearing ones.

The results of this determination in production have led us to double cast the play with hearing and Deaf actors.

The Deaf actors, working with Director of Artistic Sign Language Sabrina Dennison, will have their own playing space where they can be well-lit so audiences can see their signing.

Sophocles’s rarely performed tragedy, Philoctetes, tells of a gifted archer, exiled to an Aegean island because of an agonizing, pustulous, unhealing snakebite, yet oracles have declared Troy will only fall by dint of his skill with a bow. Edmund Wilson’s seminal essay, quoted above, draws a compelling comparison between Sophocles’s misanthropic hero and the artistic temperament. The idea of the brilliant archer, whose mastery of the bow is linked directly to his hobbling infection, corresponds with our understanding of the artist beset by obsessions or manias that are integral to their artistic vision. In the same way, from Wilson’s perspective, we would not view Deafness as an affliction but as a condition that opens up new perspectives of seeing and feeling that are less accessible to hearing humans. Craig captures this view in his Thanksgiving affirmation by Knox, the Deaf son, that he is thankful not just for his Deafness, and for his homosexuality, but even for his addictions.

It is a testament to the grandeur and generosity of Craig’s worldview that he responds to the assignment of immersing himself in Deaf culture by conducting an interior inventory of his deepest concerns; Craig’s letter shares with admirable candor his own personal struggles with addiction and despair. But here is the main reason I cited Wilson’s essay on Philoctetes: When I think of the paradigm of the struggling artist, the artist I think of first is Craig Lucas. His work invariably rides the knife edge between despair and grace, grimness and hilarity, chaos and plenitude. And I Was Most Alive with You represents a culmination of artistic concerns that have consumed him for well over a decade.