From the Artistic Director: Aubergine

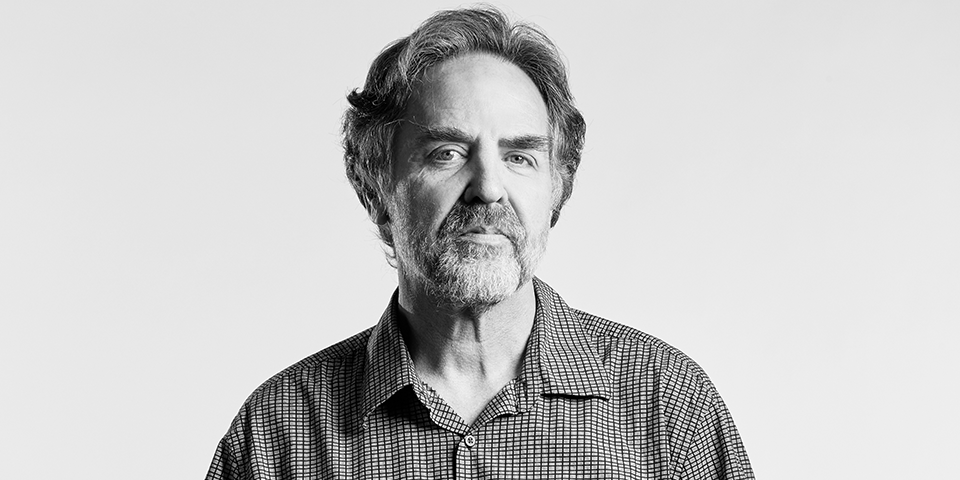

By Tim Sanford, Artistic Director

“Tragedy is a representation of an action which is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude…in the mode of dramatic enactment, not narrative — and through the arousal of pity and fear effecting the catharsis of such emotions.”

– Aristotle, The Poetics

“We hold the hands of the dying. But we are not the one holding their hands. They are the ones holding ours.”

– Julia Cho, Aubergine

Aubergine is a beautiful, important play. It has been many years since Playwrights Horizons produced Julia’s earlier play, BFE, which was only her second play produced in New York. She continued to grow as a writer, with a new play arriving in New York every couple of years: Durango at The Public, The Piano Teacher at The Vineyard, and then the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize-winning The Language Archive at Roundabout. And we have not heard from her since. So I got a little excited when Aubergine landed on my desk. I read it immediately, voraciously. About 10 minutes from the end, tears began to roll down my face. It’s such a beautiful play, so carefully wrought, deeply mined and powerful. I offered a production immediately, without even reading it a second time. It is that good.

I frequently describe plays I like as “affecting” or “moving,” but tend not to get too specific about the role emotionality plays in my hierarchy of a play’s aesthetic values. Present day critical discourse sometimes gives a wave to the emotions a play may stir, but the primary criteria for evaluating a play tend to lie in more intellectual territory. But if I’m honest, the emotional richness of a theatrical experience is integral to my enjoyment of it. And actually, that most deliberate original literary critic, Aristotle, introduces in The Poetics the centrality of emotions at the core of the dramatic event through that oft-cited and widely disputed concept of “catharsis.” The key moment in the tragic trajectory is the “anagnorisis” or recognition. Dramatic characters are always on a search, moving through time. When they cross the threshold into understanding, emotions flare in them. In a tragedy, the primary emotion is typically “fear” which inspires “pity” in the audience. Other stories might elicit other emotions, but the key to the success of the drama is this empathetic response in the audience. And the proper interpretation of this mysterious idea, “catharsis,” undoubtedly rests in the emotional surge that floods between the two worlds of drama and reality.

Dramatic characters are always on a search, moving through time.

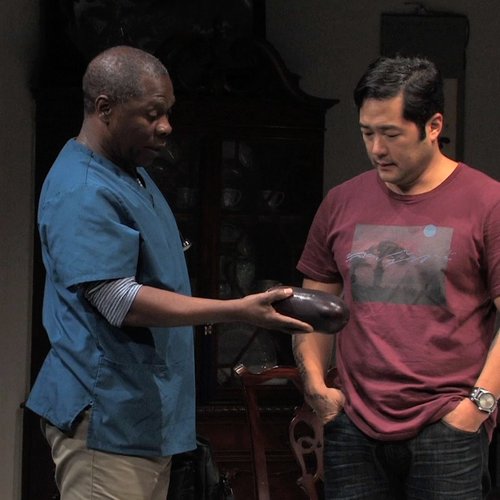

In the opening scenes of Aubergine, the first-generation Korean-American protagonist, Ray, a disaffected chef, learns that his estranged widower father is dying of liver failure. Ray sets up hospice care for him in his own apartment, including the hiring of Lucien, an experienced African émigré caretaker. Out of filial duty, Ray enlists his aggrieved ex-girlfriend, Cornelia, to call his father’s Korean younger brother, because she is the only person he knows who is fluent in Korean. Before he knows it, his uncle enters the scene, flooding Ray’s uncomprehending ears with waves of stories in Korean about their childhood and their mother, pressing exotic recipes for restorative soups into Ray’s resistant hands. So in one fell swoop, Ray’s family, his ex-girlfriend, his growing apathy towards his culinary vocation, and his Koreanness come home to roost. Food is the nexus of all these vectors. Food serves the perfect metaphorical antonym to death; it stands for the immediacy of life, for openness to joy and pleasure. But the sensory pleasures of food also unlock deep reservoirs of memories, as exemplified by the madeleine in Swann’s Way, which Adam Greenfield discusses so insightfully in his bulletin article within. But the process that gradually opens Ray up to his feelings about his father, his girlfriend, his Koreanness, and his place in the world, ultimately go beyond the Proustian epiphany of “time recaptured.” Ray’s rediscovery of food sparks in him an almost magical empathy about its almost metaphysical powers. Cooking becomes art, a vehicle that engenders a confluence of souls between the preparer and consumer of a meal. In this moment of pure evanescence, the fleeting tingle of taste buds stretches out to eternity. A window has opened in Ray. And a window opens in us. “Catharsis.”